History

Research quickly revealed Christophe Wall-Romana’s fantastic research, history, and analysis of cinepoetics.

Research quickly revealed Christophe Wall-Romana’s fantastic research, history, and analysis of cinepoetics.

"With the advent of free verse in the mid-1880s, new rhythmic and visual patterns on the page tended to foreground the corporeal, spatial, and temporal immediacy of the poem."

(Wall-Romana, p 130).

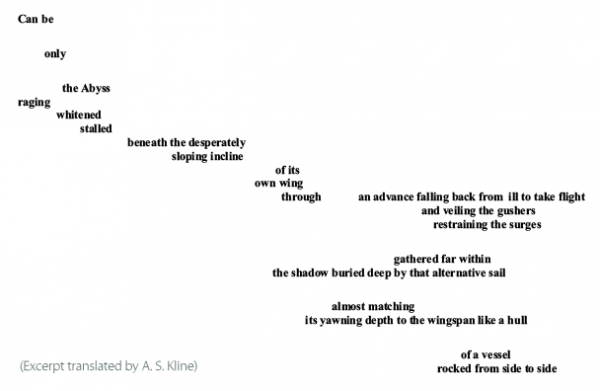

Wall-Romana suggests that French poet Stephane Mallarmé was influenced by the new medium of film. After he was introduced to cinema in 1893 Mallarme published a work of poetry Un coup de dés / A throw of the dice in 1897 that consisted of unconventionally arranged words on the page:

historymallarme

Author Dee Reynolds discusses artist’s use of imaginary space in “Symbolist Aesthetics and Abstract Art,” noting Mallarme’s layout of Un coup de des, “The structuring role of the ‘blancs’ and of the page as a spatial unit takes over the rhythmic and structural function of the ‘ancient vers’.” Mallarme varied the size of the type throughout the book, “eleven different sizes can be distinguished…In this way, Mallarme translates the hierarchical structure of the sonnet into a more radical form.”

While we do not consider printed words on the page to be cinematic. According to Wall-Romana, paper seems to have been the extent of many French poet’s experience with cinema in the late 19th century. While several French poets between 1917 and 1928 conceived of cinematic expressions of poetry, they did so on paper. Only a few were ever produced on film. Wall-Romana cites two of them, one by Antonin Artaud and the other by Robert Desnos, both of which I found online (as of Nov. 2007):

Antonin Artaud’s La coquille et le clergyman / The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928) directed by Germaine Dulac. Watch it on YouTube.com

Robert Desnos’s L’etoile de mer / The Starfish (1928) directed by Man Ray. Watch it on YouTube.com.

In watching these surrealist movies as early examples of cinepoetry, we see that the presentations are void of text on screen. The cinematography and treatment of the image is paramount. The soundtrack contains music, but no sound that is synchronous to visuals. The audience never hears nor sees the poet.

Some of these aesthetics, like sound, may be the result of technical circumstance. Yet, we know that the convention of full-screen title cards had been established by cinematic predecessors to the talkies. Therefore, we might infer that Artaud and Desnos’s cinepoems were the result of conscience decision to exclude text on screen. In watching these cinepoems, at first, there seems to be no poem attached to the visual presentation at all. This is because the visual presentation unfolds to reveal that it is the cinepoem. This may be the pivotal convention of cinepoetry – that the unfolding visual sequence itself IS the poem, presented as a visual interpretation of the written poem.

CONTINUE TO NEXT SECTION>>> CONVERGENCE